Geometric Cubism is an early 20th-century abstract art movement that marked a radical shift in the way visual reality was interpreted.

Defined by the reduction of subjects into geometric forms—such as cubes, spheres, and cones—and the representation of multiple viewpoints in a single image, it challenged the conventions of perspective, depth, and realism that had dominated Western art for centuries.

First developed in Paris between 1907 and 1914 by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Geometric Cubism laid the groundwork for modern abstract art and influenced numerous movements that followed.

It unfolded in two distinct phases: Analytical Cubism and Synthetic Cubism, each contributing new methods and ideas to the evolving language of abstraction.

Historical Origins of Geometric Cubism

| Time Period | Key Artists | Location | Significance |

| 1907–1914 | Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque | Paris, France | Challenged the traditional single-point perspective, introduced geometric abstraction |

The movement emerged at a time when photography had already begun to replace painting as a realistic visual record.

Rather than compete with photographic accuracy, artists sought to explore form, perception, and conceptual interpretation.

By dissecting forms into basic geometric shapes and flattening spatial depth, Cubism broke from centuries of visual tradition.

The label “Cubism” originated from art critic Louis Vauxcelles, who remarked in 1908 that Braque’s landscapes resembled arrangements of “cubes.” Though initially intended as criticism, the name became synonymous with a new direction in art.

Two Phases of Geometric Cubism

Geometric Cubism developed in two major phases, each with distinct visual characteristics and conceptual aims.

Analytical Cubism (1908–1912)

Characteristics

Purpose

Limited color palette (browns, grays, ochres)

Emphasize structure over decorative appeal

Fragmented, overlapping planes

Represent objects from multiple angles simultaneously

Reduced detail and realism

Focus on the internal structure and form

Flattened perspective

Challenge traditional spatial illusion

Analytical Cubism was primarily concerned with analyzing and deconstructing subjects, often still-life or portrait compositions.

The artists minimized color to avoid distraction from form and used a complex arrangement of intersecting planes to explore different viewpoints.

Synthetic Cubism (1912–1914)

Characteristics

Innovations

Use of collage and mixed media

Introduced non-traditional materials like newspaper and wallpaper

Brighter, more diverse color palette

Shifted focus from analysis to construction

More recognizable forms

Aimed for visual clarity and accessible composition

Simpler, flatter shapes

Moved toward symbolic representation rather than realism

In contrast to the intellectual approach of Analytical Cubism, Synthetic Cubism was more playful and accessible.

Artists began to synthesize forms rather than fragment them, using cut-out shapes and collage elements to reconstruct images.

Defining Characteristics of Geometric Cubism

The visual language of Geometric Cubism is distinct and easily recognizable. Several core elements define the movement:

Feature

Description

Multiple Perspectives

A single composition presents several viewpoints of the same subject

Geometric Simplification

Objects are broken down into basic forms—cubes, spheres, cones, cylinders

Fragmentation

Forms are dissected and shown as overlapping, intersecting planes

Flattened Space

Spatial depth is compressed or eliminated, emphasizing the two-dimensional surface

Limited Early Color Use

Muted tones were used in early phases to draw focus to form and structure

Emphasis on Form

Structural integrity and form outweigh visual accuracy

These features combined to present a version of reality that emphasizes how we perceive rather than what we perceive. The goal was not imitation but exploration.

Key Artists and Their Contributions

While Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were the undisputed pioneers of Geometric Cubism, the movement was enriched and expanded through the contributions of several other artists.

Each brought unique methods, perspectives, and visual approaches that helped push Cubism into new directions, reinforcing its legacy as one of the most groundbreaking developments in modern art.

Pablo Picasso

View this post on Instagram

He is often considered the central figure of Cubism. His 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is widely regarded as the turning point that laid the groundwork for the movement.

In this piece, Picasso broke away from classical ideals of beauty and realism, opting instead for angular forms and mask-like faces inspired by African and Iberian art.

This radical visual language introduced the concept of multiple viewpoints within a single frame, a defining principle of Cubism.

Throughout the Analytical and Synthetic phases, Picasso continued to experiment with form, space, and composition, contributing a vast body of work that consistently challenged traditional artistic expectations.

Georges Braque

Often working in close collaboration with Picasso during the formative years of Cubism, played an equally vital role in developing the movement’s visual and conceptual language.

While Picasso brought a daring, sometimes chaotic energy to Cubism, Braque approached the movement with more restraint and precision.

He was instrumental in refining the techniques of Analytical Cubism, particularly through the use of monochromatic palettes and tightly interlocking planes.

Braque is also credited with introducing collage elements into Cubism, a hallmark of the Synthetic phase. His willingness to incorporate materials like wallpaper and printed text onto the canvas opened new avenues for texture, surface, and meaning in modern art.

Juan Gris

@tik.t.art Juan Gris was a Spanish painter and one of the prominent figures in the Cubist art movement. He was born as José Victoriano González-Pérez on March 23, 1887, in Madrid, Spain, and adopted the pseudonym “Juan Gris” as a professional artist. Gris initially studied engineering at the Madrid School of Arts and Sciences but later moved to Paris in 1906 to pursue a career in art. In Paris, he became associated with avant-garde artists like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Fernand Léger. He was greatly influenced by the Cubist movement, which sought to depict objects and scenes from multiple perspectives, breaking them down into geometric shapes and fragmented forms. Gris’ style within Cubism was characterized by his precise and meticulous approach to composition. He often used a more muted color palette than some of his contemporaries and incorporated elements of collage into his paintings. His works typically included still life subjects, such as musical instruments, newspapers, and bottles, which he deconstructed and reassembled in a Cubist manner. Some of his notable works include “Still Life with a Guitar” (1913), “Portrait of Pablo Picasso” (1912), and “The Open Window” (1921). Tragically, Juan Gris’ career was cut short when he died of kidney failure on May 11, 1927, in Boulogne-Billancourt, France, at the age of 40. #art #artist #painter #painting #cubist #cubism #juangris ♬ Together – Special Edition – Matthew Halsall

Spanish painter closely associated with Synthetic Cubism, introduced a more structured and harmonious approach to the movement. His work is often seen as a formal bridge between the abstraction of early Cubism and the more decorative tendencies of later modernist styles.

Gris emphasized clarity of composition and the use of brighter, more varied colors. His paintings are characterized by their clean lines, calculated balance, and architectural precision.

Unlike the more intuitive experiments of Picasso and Braque, Gris’s work followed a logical and deliberate process, making him a critical figure in the intellectual expansion of Cubism.

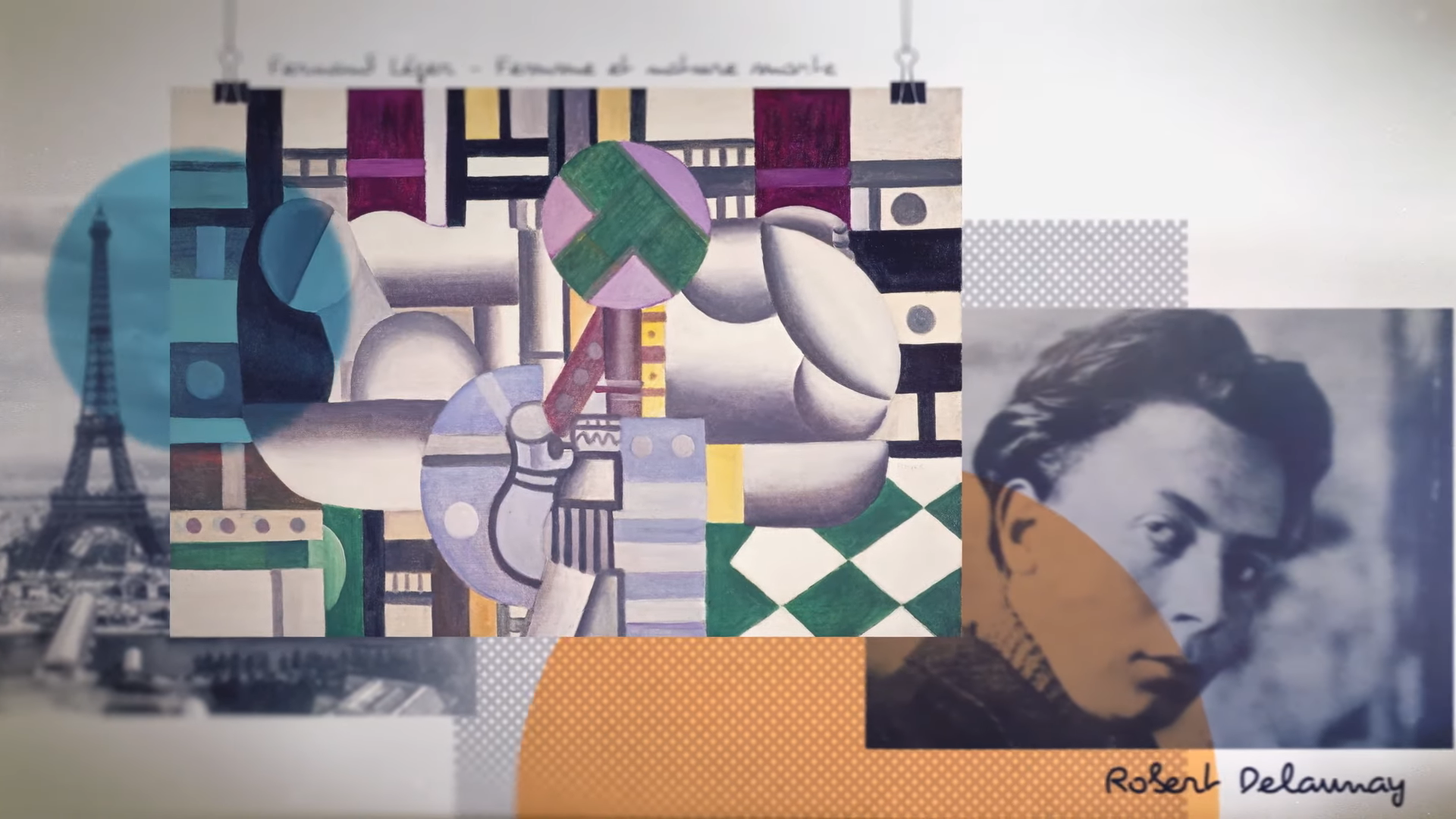

Fernand Léger

He brought a distinctive interpretation to Cubism, one that merged geometric abstraction with the rhythms of the modern industrial world. He introduced forms that were more cylindrical and tubular, reflecting an interest in machinery, technology, and the aesthetics of the mechanical age.

Léger’s work often features bold colors, stylized figures, and repeated shapes that suggest movement and synchronization.

His version of Cubism was less concerned with deconstructing form and more focused on synthesizing it with the dynamic energy of contemporary life. Through this mechanistic lens, Léger helped position Cubism as a precursor to future movements that embraced modernity and progress.

Influence on Later Abstract Art Movements

Geometric Cubism did not exist in isolation. Its core principles—fragmentation of form, geometric abstraction, and multiple perspectives—formed the conceptual bedrock for several influential abstract art movements that emerged in the decades that followed.

These movements absorbed Cubist ideas, adapted them to new cultural contexts, and extended their implications far beyond the early 20th-century art world.

Futurism

Emerged in Italy around 1909, took inspiration from Cubism’s treatment of space and form but directed it toward an entirely different goal: the depiction of movement, energy, and the industrial future.

Where Cubism focused on static objects viewed from multiple angles, Futurism sought to capture speed and dynamism.

Artists like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla embraced Cubist fragmentation but used it to show continuous motion and the mechanical pulse of modern life.

The influence is clear in their approach to disassembling and reassembling subjects in a way that mimicked velocity and force.

Constructivism

Born in Russia shortly after the 1917 Revolution, also borrowed heavily from the visual language of Cubism. Constructivist artists, including Vladimir Tatlin and El Lissitzky, adopted geometric forms and spatial arrangements reminiscent of Cubist compositions.

However, their work was driven by a utilitarian ethos—they believed art should serve a social and political purpose.

Constructivism used abstraction and geometry not for aesthetic exploration alone, but to reflect industrial production, collective ideology, and scientific rationality.

The Cubist emphasis on structure and spatial relationships translated seamlessly into Constructivist principles that treated art as a functional part of life and society.

De Stijl

Introducing Mondrian Toy Face, available for 3 ETH.

Piet Mondrian was a Dutch artist who is best known for his abstract paintings composed of straight lines, primary colors, and white space. He was a leading figure in the De Stijl movement, which aimed to create a universal… pic.twitter.com/d3udD882Dl

— Amrit Pal Singh (@amritpaldesign) May 4, 2023

Dutch movement led by artists like Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg took Cubism’s geometric tendencies to an extreme level of refinement.

While Cubism fragmented form to explore different viewpoints, De Stijl aimed to reduce visual language to its most essential components: vertical and horizontal lines, and primary colors.

The movement sought universal harmony and balance through strict abstraction, stripping away all representational content.

Mondrian’s compositions, with their grids and color blocks, can be seen as the logical conclusion of Cubist simplification—an art entirely detached from the visible world but deeply rooted in the formal investigations that Cubism began.

Conclusion

Geometric Cubism fundamentally altered the trajectory of modern art. By introducing multiple perspectives, abstracting forms into geometric structures, and emphasizing the canvas as an autonomous visual space, it dismantled traditional approaches and encouraged innovation.

Its evolution from the cerebral fragmentation of Analytical Cubism to the constructive play of Synthetic Cubism reflected broader changes in artistic priorities—from observation to conceptualization, from imitation to invention.

The movement’s legacy is seen not only in the abstract movements that followed but also in the continued relevance of its ideas in contemporary visual culture. Geometric Cubism was not merely a stylistic shift—it was a comprehensive reevaluation of what art could be.